Author: Dr Chan Beng Kuen

Date: November 2010 Issue

Original Blog Link: Link

Welcome to Ortho Insider, a publication by Orthopaedics International and Sports Medicine International. It is a sister publication of “Spine Clinic”, which is by Orthopaedics International and Neurosurgery International. This quarterly publication is aimed at providing family doctors with relevant and interesting information to highlight developments in the fast-changing world of orthopaedics and sports medicine. We hope you enjoy this and subsequent issues.

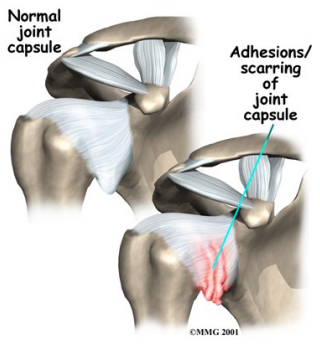

The common form of “frozen shoulder” we see in our practice is adhesive capsulitis. It is a syndrome defined as idiopathic painful restriction of shoulder movement that results in global restriction of the glenohumeral joint. This condition is characterized by gradually progressive, painful restriction of all joint motion with spontaneous restoration of partial or complete motion over months to years. It tends to occur in patients older than 40 years of age and most commonly in patients in their 50s and in women. Fifteen percent of patients develop bilateral disease.

Some systemic diseases such as diabetes, hyperthyroidism and rheumatoid arthritis are also associated with secondary adhesive capsulitis and should be considered in a patient with limited range of motion of the shoulder.

The initial discomfort is described by many patients as a generalised shoulder ache. The pain, which may radiate both proximally and distally, is aggravated by movement and alleviated with rest. Sleep is usually disturbed by the pain if they roll onto the affected shoulder. This condition progresses to one of severe pain accompanied by stiffness and decreased range of motion.

The physical examination may reveal muscle spasm and diffuse tenderness about the shoulder joint and the deltoid muscle. Passive and active range of motion in all planes of shoulder movement is decreased. The diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is primarily clinical. Osteoarthritis, calcific tendinitis and bony metastases may be detected on plain radiographs. X-rays of patients with early adhesive capsulitis are usually normal.

The natural history of adhesive capsulitis and its clinical course is divided into 3 stages: the painful stage, the adhesive stage and the recovery stage. Each stage is between 3 to 6 months with a gradual increase in range of motion in the latter stage. Complete recovery, however, is infrequent. The external rotation range of motion improves first, followed by abduction and internal rotation.

In patients with adhesive capsulitis, the goal of treatment is pain reduction and preservation of shoulder mobility. It is essential to “break” the pain cycle. Adequate analgesia is necessary for successful treatment in this phase. Physical therapy done at home with simple “Codman shoulder exercises” or with a physiotherapist is encouraged.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help relieve pain and inflammation. Analgesics and muscle relaxants are helpful in the early stages of the disease when muscle spasm is predominant. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are used in affected patients to relieve pain and permit a more vigorous physical therapy routine. The usual dosage is 20 to 30 mg of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) with 2 mls of 1 percent lignocaine.

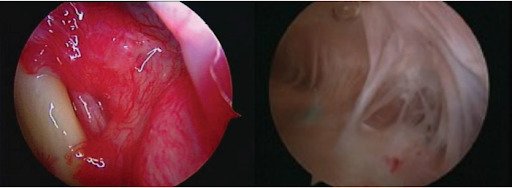

Surgical intervention should be considered when physical therapy and injections fail (no improvement after 6 weeks of therapy). Manipulation under general anesthesia is used in the patients in the second stage who do not respond to non-surgical treatment.

For patients with loss of motion refractory to closed manipulation or in the late stage of adhesive capsulitis, arthroscopic capsular release has been shown to improve motion with minimal operative morbidity. Controlled release of the adhesions under direct vision allows preservation of the subscapularis muscle and minimizes bleeding. Concomitant rotator cuff repair can also be carried out.

INSIGHTS INTO BONE IMAGING: NONINVASIVE ASSESSMENT OF BONE STRENGTH IN OSTEOPOROSIS – Prof Roland D. Chapurlat

The screening of individuals at risk for fragility fracture is generally based on the measurement of areal bone mineral density (aBMD) using absorptiometry (DXA) and on clinical risk factors. However, it has been shown that more than half of the women who will sustain a fragility fracture do not have a T-score below -2.5. It is likely that this undetected risk is associated with impaired bone architecture. So, we need to develop other techniques allowing for studying architectural characteristics, which may be considered as surrogates of bone strength, High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) is one of these innovative techniques.

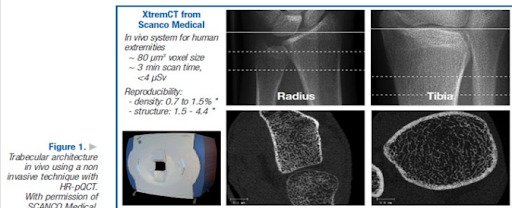

This type of machine measures cortical and trabecular volumetric bone mineral density (vBMD) at the distal radius and tibia in about 3 minutes at each site. The image definition can reach 82 mm in vivo, with excellent precision, as the coefficients of variation range from 0.7 to 1.5% for density variables and from 2.5% to 4.4% for architectural parameters (Figure 1) ^1.

In a case-control analysis, it has also been shown that decreased cortical and trabecular vBMD at the distal radius and tibia was associated with the risk of the various types of fragility fractures, independently of aBMD. At the distal tibia, cortical thickness (Ct.Th) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) were also predictive of osteoporotic fracture.Bone strength can also be approached using finite element analysis (FEA). In a case-control study with HR-pQCT images of the distal radius, mechanical properties assessed with microFEA were associated with prevalent wrist fracture. ^2

Bone strength evaluated with microFEA performed with radius and tibia images was also associated with vertebral and nonvertebral fractures, in a larger case-control analysis,3 showing that distal bone sites can be used to predict all types of fragility fractures. In a principal component analysis^3, roughly half of the variance in fracture risk is due to the parameters classified as bone strength and quantity.

A recent randomised trial comparing the effects of strontium ranelate with those of alendronate using the HR-pQCT has shown that differences in Ct.Th and trabecular bone volume (BV/TV) could be detected. This is a promising finding for trials of future compounds.

1. Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, et al. In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90: 6508-6515.

2. Boutroy S, Van Rietbergen B, Sornay-Rendu E, et al. Finite element analysis based on in vivo HR-pQCT images of the distal radius is associated with wrist fracture in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:392 -399.

3. Keaveny TM, Hoffmann PF, Singh M, et al. Femoral bone strength and its relation to cortical and trabecular changes after treatment with PTH, alendronate, and their combination as assessed by finite element analysis of quantitative CT scans. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(12):1974-1982.